NordenBladet – What were gender roles like during Viking times? A Norwegian archaeologist Marianne Moen thinks we often misinterpret the past based on our current cultural assumptions. Men and women had more similarities than differences, she says. Moen studied the contents of Viking graves for her doctoral dissertation. “I think we need to move away from distinguishing between men’s and women’s roles during the Viking times,” she said. Moen has completed her PhD on Viking Age gender roles at the University of Oslo. Her research shows that upper-class men and women generally were buried with the same types of items — including cooking gear.

Moen went through the contents of 218 Viking graves in Vestfold*, a county on the southwest side of Oslo Fjord, and sorted the artefacts she found according to type. Many of the graves were richly equipped with everything from cups and plates to horses and other livestock. Archaeologists often assume that Viking women were responsible for the house and home, while men were merchants and warriors. However, tools and items associated with housekeeping were fairly equally distributed between men and women in the Vestfold graves. “The key is a good example. It is often considered to be the symbol of a housewife,” Moen said. Nonetheless, almost as many men’s graves had keys as women’s graves. “It might be time to change the story a bit,” she said.

Men were just as likely to be buried with cooking equipment as women. Ten graves containing cookware were men’s graves, while eight were women’s. Moen likes that fact. It means that men also made food, she thinks. “My interpretation is that cooking equipment indicates hospitality. This was very important during Viking times,” she said, although others interpret it differently.

The Gokstad Ship**, the large ship displayed at the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, was part of a man’s grave and also contained a large array of cooking equipment. “These finds were often excused as being because men needed to make their own food on long voyages,” Moen says.

Not everyone agrees with Moen’s interpretation. Just because men chose to bring cookware into the afterlife doesn’t necessarily mean that they did the cooking in their own home, says archaeologist Frans-Arne Stylegar. Stylegar was previously the county conservator for Vest-Agder, the southernmost county in Norway. He currently works with cultural preservation and urban planning at the consulting firm Multiconsult. “It is difficult to translate the persona who is idealized in burial customs into actual historical reality. It’s almost a philosophical question,” he says.

Moen also thinks there is a stark difference between life and death when it comes to gender roles. But she also thinks that the items that people were buried with have some relation to what real life was like during those times.

She reminds us that tools and equipment aren’t just something that Vikings were buried with. These items were also found in houses, although without the ability to determine who used them.

Stylegar thinks that Moen’s PhD thesis was well done and that she makes a convincing case that there wasn’t much difference between the way upper-class Viking men and women were buried. He has studied several Viking graves in Vestfold previously, and isn’t very surprised by this conclusion. “I’ve gotten this impression previously, but she shows it very clearly,” he said.

However, from his own work in Vestfold, he had the impression that farmers were much more concerned with marking gender in their graves than the upper-class citizens, although he points out that this was not the focus of his research.

There are still a few clear differences between genders for the elite. Men generally have weapons in their graves, while women have jewellery and textile tools, as Moen’s work shows.

Here’s what Vikings were buried with

Viking men and women still had more similarities than differences in their graves, Moen said. More than 40 per cent of the male graves contained jewellery such as brooches and beads. The men also have what seem to be toiletries in their graves, including tweezers and razors likely used for personal grooming.

Interpreting the past through a modern lens

Moen wonders where the idea that there was clear gender differentiation in the past comes from. Other researchers have pointed out that many of the items retrieved from graves in the early 1900s were interpreted based on the cultural perspectives of those times, in the same way that Moen now sees the artefacts from her modern perspective. She calls herself a gender archaeologist, and wants to challenge other archaeologists’ interpretations of Viking culture. But entrenched perceptions among experts can be difficult to change, she says. “I encounter quite a bit of scepticism. There are quite a few researchers who are very set in their opinion on gender when it comes to work-related roles,” Moen said.

She thinks part of the reason for this is that it is much easier to relate to a version of history that is in keeping with our modern expectations, “a version of history where men and women have specific roles in society,” she said. “In general, in Viking Age studies, artefacts found in graves are interpreted as being connected to the person buried in the grave. This shouldn’t change for cases where artefacts don’t meet modern expectations of what a man or woman would have in their grave,” Moen said.

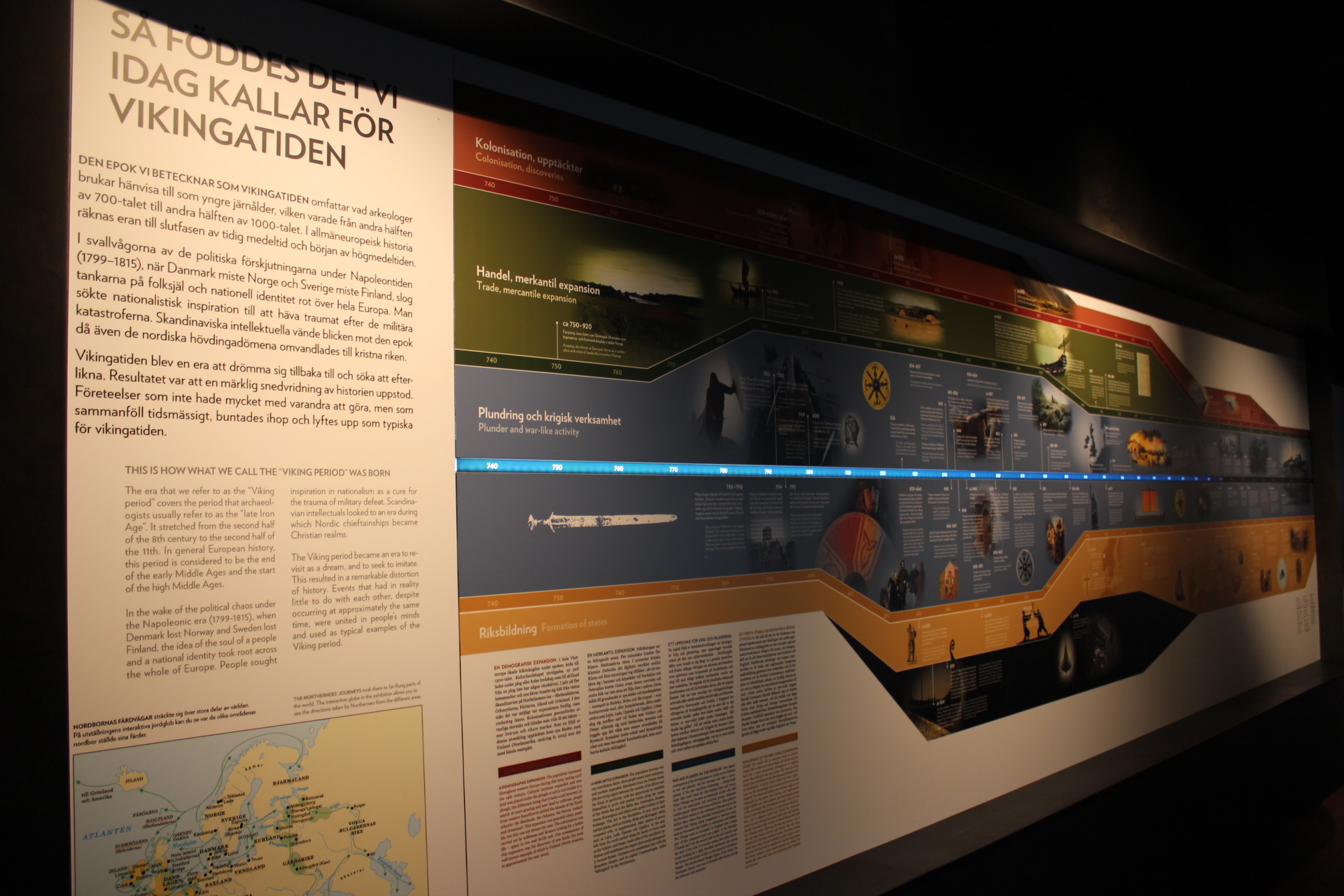

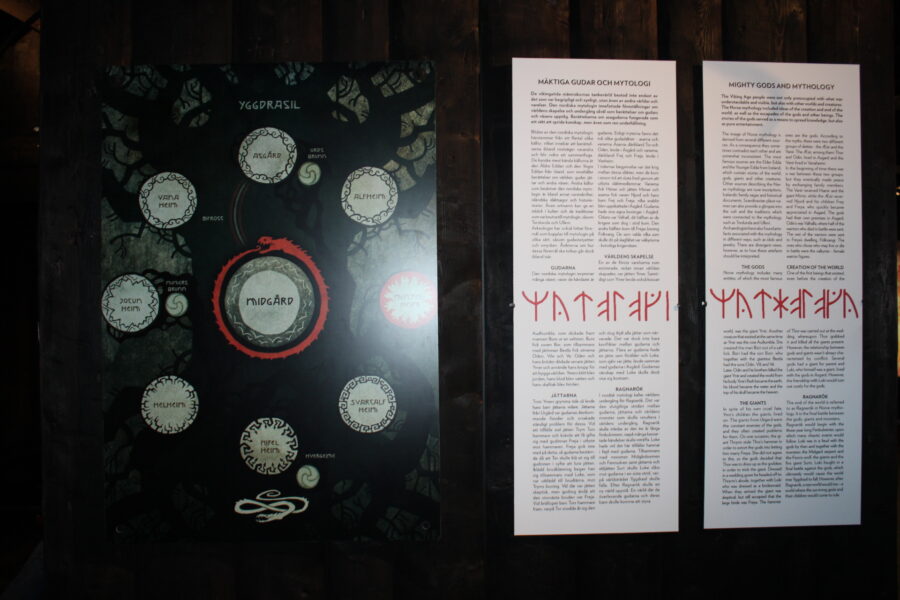

Photos: The Viking Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. 4x NordenBladet/Helena-Reet Ennet

What people ask about the death and funeral of the Vikings

What is a Viking funeral called?

A Norseman could also be buried with a loved one or house thrall, or cremated together on a funeral pyre. The most sumptuous Viking funeral discovered so far is the Oseberg Ship burial, which was for a woman (probably a queen or a priestess) who lived in the 9th century.

What is a Viking boat grave?

Two Viking boat graves have been uncovered in Sweden in what archaeologists are describing as a “sensational” discovery. One grave, which was intact, contained the remains of a man, a horse and a dog, according to archaeological service Arkeologerna (The Archaeologists), which announced the finds.

Why would a viking be buried?

When it comes to the burial, the Vikings would bury the ashes of their dead in graves or even under piles of rocks. Goods and belongings would be buried with the deceased, suitable to match their life.

Is a Viking funeral legal?

Burial at sea is legal under certain circumstances, subject to various rules. … Scattering ashes at sea is perfectly legal though people might want to inform the coastguard that they’re sending a small burning vessel into open water…just in case! Real Viking funerals, however, are perfectly legal.

Did Vikings burn their dead in boats?

The dead were burnt or buried in their daily clothes, and are usually buried along with his or her personal belongings. Sometimes the dead were buried lying in a boat or a wagon. Cremation was the more common of the two burial practices in the early Viking Age.

What happens when a Viking dies?

Vikings: Afterlife and Burial. When Vikings died they believed they would go to Valhalla***, where they would spend their afterlife. Warriors who had died bravely would be carried by the Valkyries to Valhalla. There they would be welcomed to the afterlife by the god Odin, with whom they would feast every night.

What is a funeral boat?

A ship burial or boat grave is a burial in which a ship or boat is used either as a container for the dead and the grave goods, or as a part of the grave goods itself. If the ship is very small, it is called a boat grave.

When was the Oseberg ship discovered?

1904. The famous Norwegian Viking ship, the Oseberg ship, was built in AD 820, buried in a grave mound 14 years later, and excavated in 1904. Shortly after the excavation, the 21.5m long and 5.0m wide ship was re-assembled and exhibited at the Viking Ship Museum, in Bygdøy, Oslo.

How did Vikings honor their dead?

How Did The Vikings Honor Their Dead? Most Vikings were sent to the afterlife in one of two ways—cremation or burial. Cremation (often upon a funeral pyre) was particularly common among the earliest Vikings, who were fiercely pagan and believed the fire’s smoke would help carry the deceased to their afterlife.

How did Vikings say goodbye?

Etymology. Originally a Norse greeting, “heil og sæl” had the form “heill ok sæll” when addressed to a man and “heil ok sæl” when addressed to a woman. Other versions were “ver heill ok sæll” (lit. be healthy and happy) and simply “heill” (lit. healthy). The Norwegian adjective heil (also hel) is related to the English adjective whole/hale. The Norwegian verb heile (also hele) is related to the English verb heal through their common origin, the Germanic word stem haila-, from which also the German verb heilen and the adjective „heile“, i.e. functioning / not defect descends. The Norwegian adjective sæl, meaning happy or glad, is in Old English documented only in the negated variant unsǣle, meaning evil.

___________________________________________________________

* Vestfold is mentioned for the first time in a written source in 813, when Danish kings were in Vestfold to quell an uprising amongst the Fürsts. There may have been as many as six political centers in Vestfold. At that time Kaupang, which was located in Tjølling near Larvik, had been functioning for decades and had a chieftain. Kaupang, which dates from the Viking Era, is believed to be the first town in Norway, although Tønsberg (which dates from ca. 900) is the oldest town in Norway still in existence. At Borre, there was a site for another chieftain. That site held chieftains for more than one hundred years prior to 813.

The stone mounds at Mølen have been dated to the Viking Age. The mounds at Haugar in present-day Tønsberg’s town centre have been dated to the Viking period. At Farmannshaugen in Sem there seems to have been activity at the time, while activity at Oseberghaugen and Gokstadhaugen dates from a few decades later.

An English source from around 890 retells the voyage of Ottar (Ottar fra Hålogaland) “from the farthest North, along Norvegr via Kaupang and Hedeby to England”, where Ottar places Kaupang in the land of the Dane – danenes land. Bjørn Brandlien says that “To the degree that Harald Hårfagre gathered a kingdom after the Battle of Hafrsfjord at the end of the 9th century – that especially is connected to Avaldsnes – it does not seem to have made such a great impression on Ottar”. Kaupang is mentioned under the name of Skiringssal (Kaupangen i Skiringssal) in Ottar’s tales.

By the 10th century, the local kings had established themselves. The king or his ombudsman resided in the old Royal Court at Sæheim i Sem, today the Jarlsberg Estate (Jarlsberg Hovedgård) in Tønsberg. The farm Haugar (from Old Norse haugr meaning hill or mound) became the seat for Haugating, the Thing for Vestfold and one of Norway’s most important place for the proclamation of kings. The family of Harald Fairhair, who was most likely the first king of Norway, is said to have come from this area.

The Danish kings seem to have been weak in Vestfold from around the middle of the 9th century until the middle of the 10th century, but their rule was strengthened there at the end of the 10th century. The Danish kings seem to have tried to control the region until the 13th century.

** The Gokstad ship is a 9th-century Viking ship found in a burial mound at Gokstad in Sandar, Sandefjord, Vestfold, Norway. It is currently on display at the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo, Norway. It is the largest preserved Viking ship in Norway. The site where the boat was found, situated on arable land, had long been named Gokstadhaugen or Kongshaugen (from the Old Norse words konungr meaning king and haugr meaning mound), although the relevance of its name had been discounted as folklore, as other sites in Norway bear similar names. In 1880, sons of the owner of Gokstad farm, having heard of the legends surrounding the site, uncovered the bow of a boat while digging in the still frozen ground. As word of the find got out, Nicolay Nicolaysen, then President of the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Norwegian Monuments, reached the site during February 1880. Having ascertained that the find was indeed that of an ancient artifact, he liaised for the digging to be stopped. Nicolaysen later returned and established that the mound still measured 50 metres by 43 metres, although its height had been diminished down to 5 metres by constant years of ploughing. With his team, he began excavating the mound from the side rather than from the top down, and on the second day of digging found the bow of the ship.

*** In Norse mythology, Valhalla (Old Norse Valhöll “hall of the slain”)is a majestic, enormous hall located in Asgard, ruled over by the god Odin. Chosen by Odin, half of those who die in combat travel to Valhalla upon death, led by valkyries, while the other half go to the goddess Freyja’s field Fólkvangr. In Valhalla, the dead warriors join the masses of those who have died in combat (known as the Einherjar) and various legendary Germanic heroes and kings, as they prepare to aid Odin during the events of Ragnarök. Before the hall stands the golden tree Glasir, and the hall’s ceiling is thatched with golden shields. Various creatures live around Valhalla, such as the stag Eikþyrnir and the goat Heiðrún, both described as standing atop Valhalla and consuming the foliage of the tree Læraðr.

Valhalla is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, in the Prose Edda (written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson), in Heimskringla (also written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson) and in stanzas of an anonymous 10th century poem commemorating the death of Eric Bloodaxe known as Eiríksmál as compiled in Fagrskinna. Valhalla has inspired various works of art, publication titles, and elements of popular culture, and has become a term synonymous with a martial (or otherwise) hall of the chosen dead.

More about Norse and Scandinavian mythology:

EXHAUSTIVE OVERVIEW: who were the ancient Scandinavian origin Vikings and when was the time of the Vikings?

Stockholm´s museums: The Viking Museum – tourist info, guides, pictures

Featured image: Viking age. The Viking Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. (NordenBladet/Helena-Reet Ennet)

Reference: Marianne Moen: Challenging Gender. A reconsideration of gender in the Viking Age using the mortuary landscape. Doctoral thesis at the Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History, University of Oslo, 2019